The true story behind the film Wicked Little Letters.

Thanks for reading Stranger Than Fiction: True life Stories! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

The real-life mystery surrounding the Littlehampton poison pen letters wouldn’t be out of place in an Agatha Christie thriller.

It has all the elements: mystery, small-town life, snobbery, prejudice, and plenty of wicked deeds conducted behind closed doors. The timeline of events spans the relationship between two young women whose close friendship would eventually spiral into something chaotic and terrible.

The Littlehampton libelous letter mystery was recently adapted into a critically acclaimed comedy-drama starring Olivia Coleman. However, the real story is much darker, lacks a Hollywood ending, and although justice was served in the end, lives were ruined along the way.

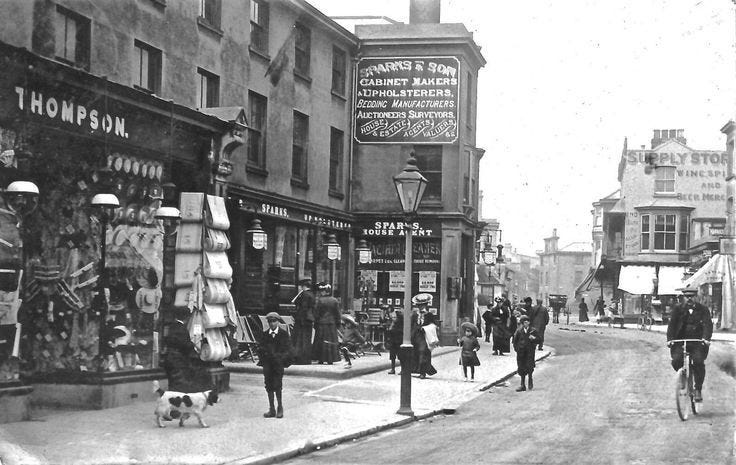

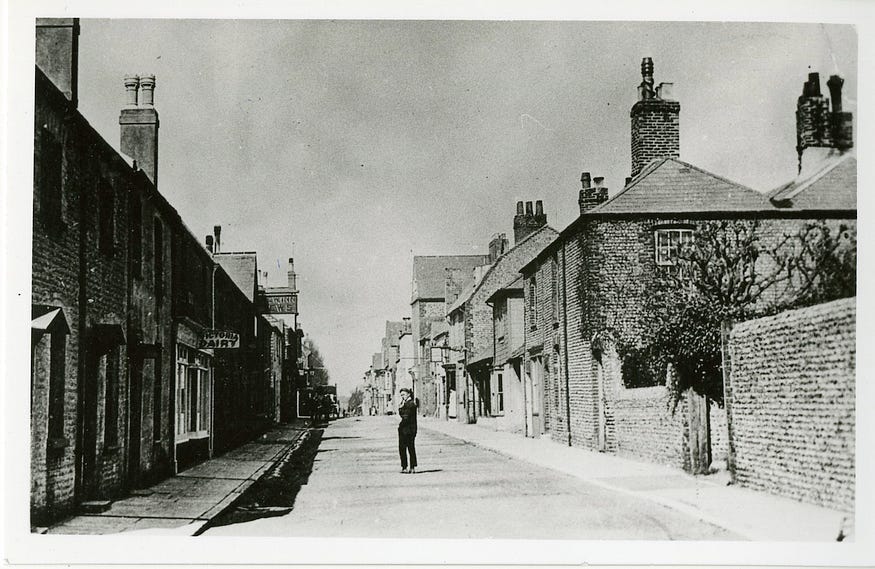

In 1918, Littlehampton was a picturesque English seaside town with a population of just under 10,000. Rose and Bill Goodins and their two children had recently moved into 49 Western Road, a small cottage that shared a garden space with the Swan family.

The Swan household consisted of elderly parents Mary Ann and Edward, daughter Edith, and her two older brothers, Stephen and Ernest. They were a respectable working-class family living a quiet ordinary life, but all that was about to be thrown into turmoil.

A fractured friendship

To begin with, both families got along well and Edith and Rose, both in their twenties, became especially friendly. They would swap cookery recipes and knitting patterns and genuinely seemed to like each other. Over time, though, their friendship became acrimonious.

The communal garden was a major cause of tension, and the Swans began complaining about the Gooding’s bins, which were often overflowing and smelly. Rose retaliated by bringing up the strong smell of the rabbits the Swans kept for meat.

The bad feeling came to a head one Easter Sunday in 1920 when a ferocious row between Rose and Bill spilled out into the garden. Rose could be heard cursing Bill as she accused him of fathering her sister’s third child (Rose’s sister Ruth, along with her three children, had moved in with them). It was Rose’s bad luck that she was overheard by Edith Swan and another neighbor, Mr. William Burkin, who claimed he had never heard such disgusting language in all his life.

Soon after the infamous row, Edith made a report to the National Society for the Protection of Children (NSPCA) claiming that she witnessed Rose beating her sister’s baby. (This was subsequently investigated by the organization, and they found the baby well and healthy).

When Did the Poison Pen Letters Start?

The first letter landed on the front doormat of the Swans within a couple of weeks of Edith’s report to the NSPCA. It seemed Edith was the target. The message read:

“you bloody old cow, mind your own business if you don’t want trouble.”

This would be followed by a slew of libelous letters and postcards aimed at Edith Swan, her family, neighbors, and customers.

What was in the letters?

The letters are still shocking even today with their heavy use of sexual imagery and swear words. The letter writer had a fondness for using the terms ‘foxy ass whore’ and ‘piss county whore’ whether referring to women or men, and they routinely made accusations of infidelity and thievery. The letters were usually signed, R, or R.G. (Rose’s initials).

One particular letter ended Edith’s engagement when it targeted her fiance Bertie Boxall, a soldier, stationed abroad in Iraq. It informed him that Edith had “committed immorality” with a local policeman and was now pregnant. Bertie was horrified and dumped Edith.

The news of the libelous letters quickly spread through Littlehampton and the community was ablaze with gossip about the perpetrator. People were outraged for Edith but there was a lot of fear as well.

Emily Cockayne in Penning Poison: A History of Anonymous Letters, found that communities became suspicious and paranoid when facing a wave of poison pen letters. The bond of trust between neighbors, who are often privy to intimate details of each other’s lives, begins to erode. The letter writer has complete control and during this period, with the advent of the Penny Post, it was cheap and easy to send anonymous letters. Cockayne argues “anonymity creates dis-inhibition”, leaving the writer’s imagination to run rampant.

The finger is pointed at Rose

The contents of the letters were of such a shocking nature to 1920s sensibilities, that it was impossible to believe that any respectable woman would have been able to conceive of, never mind employ such language.

Fingers were firmly pointed in the direction of Rose. She could be hot-headed and outspoken at times, and, she and her sister were viewed by many in Littlehampton as being “highly immoral” due to the fact they both had illegitimate children.

To cap it all, Rose had also been overheard using bad language in the Easter Day row with Bill, and most people assumed she was taking revenge for being reported to the NSPCA. Rose strongly denied any wrongdoing, but she was not believed.

A Private court case

Buoyed up by the community’s response to the letters, Edith went to the police, but they felt there wasn’t enough evidence, so she contacted a solicitor and was advised to fund a private prosecution.

This required less rigorous evidence, and ultimately, Edith was successful. In September 1920 Rose was summoned to appear before the magistrate. The hearing was essentially a comparison of the characters of Edith and Rose.

Rose was charged, but as she didn’t have bail money, she sat in jail in Portsmouth prison for three months awaiting trial before her case was tried. Although there wasn’t a shred of evidence against her at trial, she was found guilty and given a further 14 days in prison.

Rose returned home just in time for Christmas, but life did not return to normal for her. She faced a lot of hostility from her neighbors, and by now, the press had taken an interest in the story with some of the salacious details making headlines.

Incredulously, shortly after Rose’s return, the letter writer took up their pen again. Edith’s brother was accused of stealing from his work, and many of Edith’s laundry clients received letters claiming she was not to be trusted.

A Second Prosecution

In January 1921, Edith tried to get Rose convicted for the second onslaught of letters. She funded a private prosecution for the second time, which was very expensive. (You have to wonder where Edith, an ordinary working-class woman found the money to pay for this).

Rose’s solicitor tried to introduce two pieces of evidence; a chutney recipe and knitting instructions passed on to Rose by Edith, which demonstrated that Edith’s handwriting was very similar to the libelous letters. The judge refused to allow them to be shown to the jury, and yet again Rose was sentenced on nothing more than Edith’s word and the flimsiest of circumstantial evidence. On 3rd March 2021, she was sentenced to 12 months hard labor at Portsmouth prison.

Scotland Yard and a Stakeout in a potting shed

Once Rose was behind bars, life returned to normal for Edith until one afternoon while out walking, she found a notebook filled with obscenities in the same handwriting as the letters.

She posted the notebook to the police along with an explanatory note. This, however, did not produce the outcome that Edith expected. The police became suspicious because Rose, the supposed letter writer, was in jail, and Edith’s handwriting in the note was suspiciously similar to that in the obscenity-ridden notebook.

Over the next year, the local police would collaborate with top Scotland Yard inspector George Nichols to sniff out the true culprit. Nichols was suspicious of Edith, and he thought her “possibly wrong in the head.” In August 1921 he recruited Gladys Moss (who was West Sussex’s very first female officer) to keep an eye on The Swans, and this proved to be a good move. Hiding in a potting shed, she spotted Edith drop a piece of paper at the back door of neighbor Violet May who lived in the police cottage. It was a libelous letter addressed to Violet May’s husband:

“to fucking old bastard May, 49 Western Road. You bloody foxy ass bastard, you don’t do your duty or you would find out what old four eyes brings home… from the Beach hotel”

Edith’s house was searched and blotting paper was found with writing imprints identical to the poison letters. Inspector Nichols also noticed that, when writing letters from prison, Rose would misspell basic words that were spelled correctly in the libelous letters. With the new evidence Rose’s conviction was overturned on appeal and she was compensated 250 pounds (£10,000 today).

Edith faces trial

Inspector Nichols felt that there was enough evidence for a prosecution so in December 1921 she was sent to trial.

Edith arrived at court dressed demurely wearing a smart black coat and hat with a white flower on her buttonhole. The judge refused to believe that such a respectable lady would have the ability to write such letters and the jury agreed so she was cleared of all charges.

The letters rage on

The letters raged on for the next year and became more unhinged and vicious in their attacks. The police devised another plan which involved collaborating with two Post Office Special Investigation officers.

Some stamps were marked with invisible ink and were set aside at the Littlehampton Beach Post office to be sold only to Edith Swan. Then one evening in July, Edith was observed by the officers posting two letters, one to her sister and the other addressed to the sanitary inspector.

The letters were immediately removed from the post box and Edith was called into the post office where she and the police watched as the letters with the invisible ink were placed under a lamp. Edith’s initial and a special mark appeared on the stamps proving she had written the letters.

Edith was charged on the 4th of July 1923 and brought back to court, where, despite the mounting evidence, the judge still didn’t believe she had written the letters. The jury, however, took a more pragmatic approach and resoundingly found her guilty.

Like Rose, she was sentenced to 12 months of hard labor at Portsmouth Jail. She served her sentence but would never admit her guilt.

What prompted Edith to write the letters?

The press had a field day with endless speculation as to why Edith wrote the letters with The News of the World claiming she exhibited a type of ‘sex mania.’

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what drove Edith to send those letters. Perhaps jealousy or resentment. Edith certainly received a lot of attention through her apparent victimization. Inspector Nichols had believed there was some form of mental illness behind Edith’s actions.

Emily Cockayne when analyzing women’s role in poison pen letters around that time, found:

“These letters were more obviously connected to the frustrations of community life for women who felt trapped in particular roles.”

Edith may have felt frustrated and longed for some excitement in her life. This doesn’t explain why she so ruthlessly targeted Rose though.

Further developments

In the end both women and their families were damaged irreparably by the letters. The stress and shame caused by the court case and accusations would be overwhelming in a time where respectability was everything.

The census of 1939, shows, that Rose was still living in Littlehampton with her family but friends said that she suffered from insomnia and found it difficult to pick up the pieces of her life. Edith was found to be living in an institution for the ‘incapacitated’ in Worthing, where she stayed for the remainder of her life.

If you have any thoughts about this case, please leave them in the comments.

Sources:

West Sussex Record Office: Libellous letters in Littlehampton

Emily Cockayne: Penning Poison: A History of Anonymous Letters,

Comments